Part Two: My Grandfather - the Latvian Refugee

The true story behind The Baker's Secret

Latvia’s History

Latvia’s history is one of oppression and occupation, but also resilience and determined strength. In Part One of this exploration into the life of my grandfather, the life that inspired my novel The Baker’s Secret, I delve into this history.

Now, it is time to uncover his story.

My Grandfather’s Story

So, where did my grandfather fit in with all of this brutal history?

Had he really aligned himself with the German Occupiers against his people?

It was time to dig deeper…

Starting with his birth certificate and his migration documentation papers, I learned a few extra facts:

My grandfather was, in fact, born Villis Kondrants (not Kondrats)

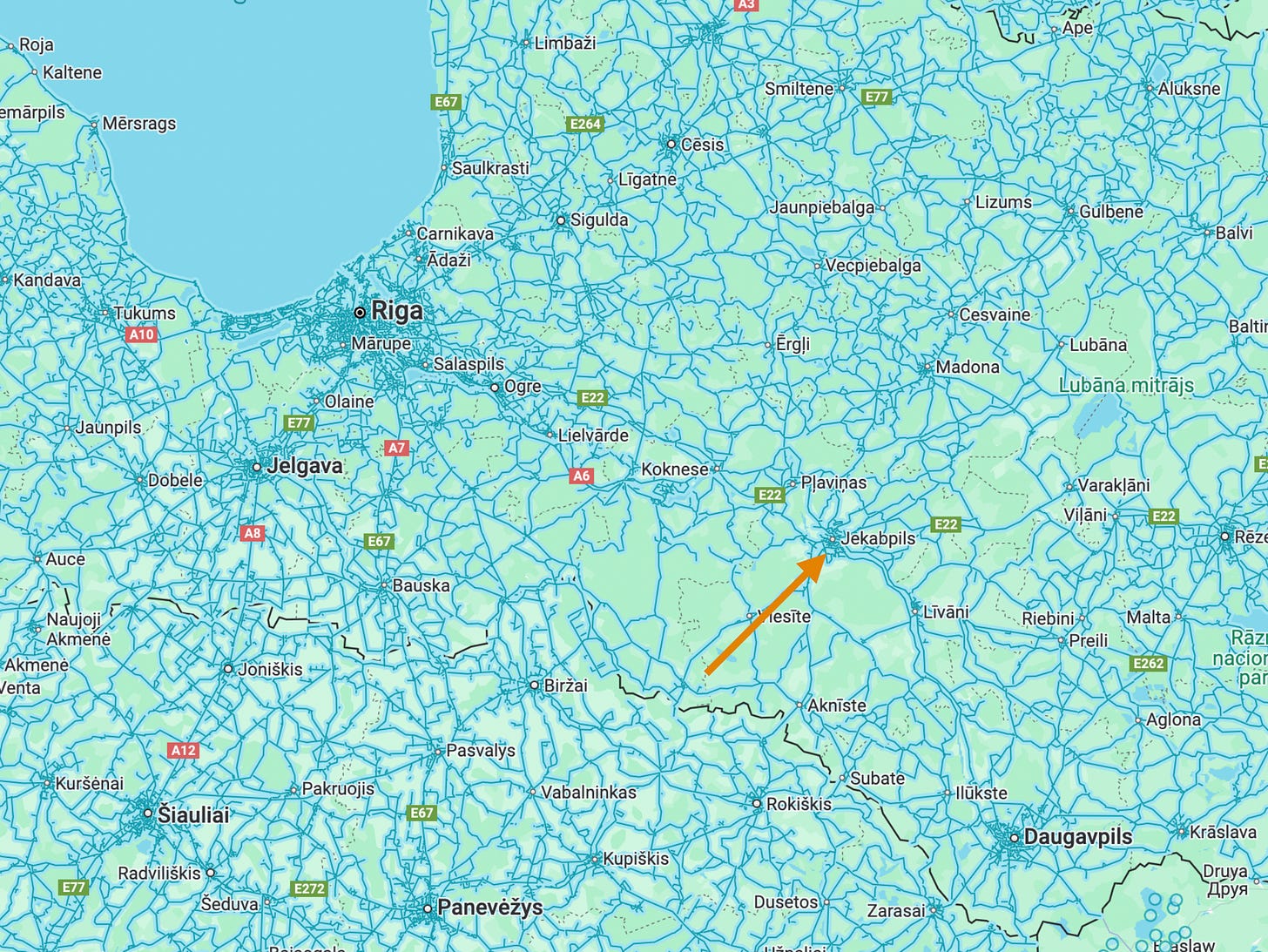

He was born on September 18, 1929 in Krustpils (coincidentally, my birthday is also September 18)

His parents were Nikolai and Berta

He travelled to Australia from Bremerhaven

Using these details, I began to piece together a timeline of his life.

Born in central Latvia in 1929, Villis’ father, Nikolai, was a baker in Jekabpils (the town on the opposite bank of the Daugava river that runs through Latvia to Krustpils where Villis was born), and his mother was Berta. He had two brothers and a sister.

Villis was 10 when the Soviets came, 11 when the German Army took over. So young…

He left some small snippets, too. Memories shared with my mommo that offer insight and context.

Once, Villis recalled that his father displayed a large framed image of Hitler in his bakery, in a place that could not be missed.

He also told of the death of his friend. The two boys were playing in the street when a soldier in his neat German field-grey uniform appeared. He drew his gun and shot Villis’ friend point-blank, with no warning. “Jew,” the soldier declared and walked away, leaving Villis alone on the cobbles with his friend’s bleeding body. He was 12 years old.

Two facts - two possible interpretations. Did Nikolai display Hitler’s image and change the family surname from the Latvian Kondrants to the Germanised Kondrats, to signify allegiance to Germany? Or to court favour with their occupiers for safety?

How did his son view this after seeing his friend murdered in cold blood?

And there was an even darker truth yet to be revealed.

Because Villis’ family did not survive the war.

Only Villis did.

The End of the War

By 1945, Hitler’s armies were crumbling. Stretched too thin, fighting a war on two fronts, his grab for domination began to falter. The Allied forces of the UK and America pushed from the West, and Russia surged from the East.

Latvia is in the East.

When the Soviet Army stormed back into Latvia, forcing Germany out in 1945, the people of Latvia quaked in fear. The memories of the Red Terror had not dissipated. Many fled, boarding boats along the Daugava and out into the bordering Baltic Sea, seeking safety in the then German-controlled port city of Danzig, modern-day Gdansk, Poland.

But the Soviet advance didn’t stop at Latvia’s border, nor Lithuania’s. As Russia swarmed through the German-occupied territories, closing in on Danzig, the Baltic refugees continued inland on foot, desperately trying to stay separate from the Soviet forces, eventually finding sanctuary in Allied-run Displaced Persons camps across now-conquered Germany. A displacement of people from across the Baltic States that came to be known as the ‘Great Dispersal’.

But Villis and his family did not flee.

They were already dead.

And Villis was in a German Forced Labour camp.

We don’t know how they died, or why. We don’t know what insult or mistake had Villis hauled away to a forced labour camp at only 15 years old. Villis would never speak of it. But these are hardly the outcomes you would expect for collaborators.

Liberated from the labour camp by the US army, Villis was sent to a Displaced Persons camp near Hamburg, formerly a Zoo, converted to a labour camp barracks during the war and now a place of refuge.

Was this when the surname changed? Villis was illiterate. Did the US Soldiers simply take the spelling of his surname from the German camp documentation? Kondrants becoming Kondrats?

So many possibilities for one clue: the spelling of a name. The change that sparked my research.

All interpretations are welcome, and somewhere within them a truth hides. But whatever that truth is, some facts remain clear: Villis lived through Soviet and German occupation, we witnessed atrocities, lost his entire nuclear family and was sent to a forced labour camp in Germany.

And he never returned to Latvia.

The Fate of the Refugees

The men and women in the Displaced Person Camps across Germany were well looked after. Dusted for lice, their medical needs attended, housed in warm and dry barracks, fed simple but plentiful rations, after five years of fear and danger, they were finally safe.

But, as Soviet Russia consolidated its hold over the Baltics and other regions that would form the USSR, they had no home to return to.

By 1946, the Allied Nations realised this was an issue. These people could not return to their countries, but they couldn’t live in temporary camps forever either. A solution had to be found.

Britain was one of the first to offer resettlement, agreeing to take a number of skilled refugees. Villis was not skilled.

Then the US enacted their own policy, mostly focused on families. Villis was alone.

In 1947, Australia opened its borders. The condition? Two years of mandatory service to the nation.

In November 1947, Villis boarded the USS General Stuart Heintzelman, the first ship to depart Bremerhaven, Germany, for the other side of the world: Australia.

Australia, my mommo, my mum

Villis arrived in Victoria, Australia, in January 1948. Peak summer, when temperatures regularly climb above 40 degrees Celsius. The high summer sun must have been a shock to a young man used to temperatures as low as -30.

He, along with the other refugees, was sent to a migrant camp in a town called Bonegilla. They were given six weeks of language lessons, then sent out to work.

Most of the Baltic refugees were sent to New South Wales to work on the Snowy River Dam Scheme. Deemed “The Beautiful Balts” by the press, they were largely welcomed and celebrated. They formed a community, working together, living together and finding a new life far away from the reach of Soviet Russia.

Villis and seven other Latvians were sent to South Australia.

He worked on the docks and then on a sewage treatment plant and was housed in a tent on the side of the road.

He was 19. He spoke little English. He was illiterate. He was alone.

But he prevailed.

At the end of his two-year service, he met a pretty young woman at a dance in a town hall, Dorothy Meyers, my mommo. Within 12 months, they were pregnant and married. Within five years, they had four children (my mum is number 3). The family moved to the Riverland, a place of fruit and nut farming. Villis got a job on the railways. A job that came with a home, a small stone cottage to house his family.

Within eight years, Villis had disappeared.

A Path to Understanding and Forgiveness

Villis abandoned my mother, her siblings and my mommo. He left them with nothing. Without his job on the railway, my mommo had to move out of the cottage. She was a single woman with four small children in a time when government assistance did not exist.

But she was a fighter. She found a job running a grocery store at the end of a railway line. A two-room building, too hot in summer, too cold in winter. But a roof over their heads nonetheless. She worked hard and somehow there was always food on the table, even if it was simply bread and cream gifted by the local dairy farmer.

Despite the hardship, this was the happiest time of my mother’s childhood, because they were all together, and despite the disruption of abandonment, my mommo made them feel safe and loved.

Learning about the past and the experiences of my grandfather opened up a path to forgiveness for my mother and understanding for me.

But the story was not yet done.